Dear Friends:

At the airport earlier this week, the person sitting at the table next to N.’s and mine spent the whole time on a Facetime call. I looked over and saw on the screen three faces along the same couch, the screen panning back and forth among them. ‘Wait! No, wait wait wait! No listen okay listen’ was the kind of stuff our tablemate kept saying at the phone at full volume, working their way into a conversation happening who knows where.

Later, walking to the exit, our elevator door opened and a couple stood front and center with their roller bags, waiting to get on. They didn’t budge when they saw us. We had to maneuver around them and their impatient scowls, as though we were in the way.

‘If I ever get a genie to grant me three wishes,’ I told N. as we walked out, ‘I’m going to wish to like other people.’ I was only half-kidding. How can anyone govern such a people? N. reminded me that few of us are our best selves in an airport. ‘I just made a complete mess trying to pour coffee into my travel mug,’ he for-instanced, owning up to being part of the problem.

What if we’re all part of the problem? That’s a question I’m more interested in these days than Who’s to blame for this fascist government we’re suffering under? It’s not ‘rudeness’ or ‘partisan divides’ I’m seeing, so much as a private sovereignty everyone seems to have an ironclad grasp on. An accommodating mindset for authoriarians.

Noting here that Shenny is its own little of fiefdom of one—except this week, when our Main Matter is a kind of open forum on midlife with my friend Beth.

Yours:

Dave

Endorsements

1. Consumer Activism

Hurting companies—in the small way any one individual can—when they hurt us feels better than continuing to give them business. This obvious thing is why Meta—who now allows anti-queer language on its platforms—is no longer on my phone. Same with Uber, who removed all references to diversity and inclusion in its latest annual report. No one in our government is able, or even willing,1 to punish companies for dismantling initiatives that repair decades of systemic racism in the U.S., so we have to do the work. And a very large number of us have to do this work together. Forbes has put together a handy compendium of who’s dropped DEI and who’s holding strong—Costco forever! It’s not always easy to join the fight, given that so many companies are doing the wrong thing it’s like good luck choosing a damn soda, but it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. Don’t fall into that idealist trap. Make the changes you can, no matter how many extra days you’ll have to wait for Amazon to ship you that thing.

2. Federal Workers

This administration is an assault on all of us save the ultra wealthy, but of course the brunt of the abuse has been to federal workers. With each shitty decree from the Department Of Unelected Creeps Hurting Everyone, thousands of workers have lost their jobs providing services to the public. This why I support the Federal Unionists Network, who are working to build solidarity and mass action among those in the public sector. And why I’ve also been reading Sabrina Imbler’s interviews on Defector with fired federal workers—from the NOAA, USDA, EPA, and other offices. Ours is, still, a government of the people, and one way we might restore that government is to focus less on the loudmouths we keep electing and more on the everyday workers just trying, like us, to do their job.

How to Avoid a Midlife Crisis

This Main Matter was inspired by a text exchange I had with Beth Sullivan of Person to Person about the tropes of the midlife crisis. Read her take here.

A few weeks back, I saw the very good Berkeley Rep production of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, starring Hugh Bonneville (whom you may know as Lord Grantham) in the title role. Vanya has spent the last 25 years of his life running the country estate owned by his brother-in-law, a retired professor who writes endless pamphlets on arcane topics that nobody reads. He’s not exactly the star of the play, Vanya, and when you look again at the title you realize only one character calls him ‘uncle’: Sonya, the professor’s daughter whose toiling on the estate has funded his academic pursuits.

For me, this made Sonya the star of the show, or at least the character I focused on. Sonya is the same age as her new step-mother, but plain, unable to attract the attention of the neighboring doctor she’s hot for. So her lot in life is Vanya’s, too: work the estate. In the final scene of the play, facing an uncertain future, she tells Vanya this:

What else can we do? We have to keep living. There are days and days and days ahead of us.

She’s too young to be having a midlife crisis, but she sure found its key anxiety.

Well let me step back a bit, because before the play, I thought of a midlife crisis as the reverse anxiety: you’re past the halfway point in your lifespan, with the bulk of your years on earth—and, more importantly, your youth—behind you. That’s the crisis: you’re closer to death than birth.2

The crisis usually manifests itself as (a) depression and/or (b) reaction formations—like when America reacted to Sept. 11’s exposing our weak defense and loathsome image abroad by putting American flags on things.

Midlife’s reaction formation is acting however you consider ‘youthful’ to be. Dating a lot, enjoying video games, seeing rock shows, not talking to a single peer around you because you’re occupied with TikTok—these don’t mean you’re going through a midlife crisis. Undertaking those things in the hope they infuse you / your spirit with youthfulness is the thing.

Young people are youthful. People in midlife crises get youthy.

Per Sonya, Forbes magazine3 is more charitable: ‘A midlife crisis is defined as a period of emotional turmoil in middle age, around 40 to 60 years old, characterized by a strong desire for change.’ Because what else lies behind the fear of days and days ahead but their sameness?

Desire for change isn’t a crisis. The inability, or refusal, to bring about the desired change, however, is.

Which helps us see some causes:

A fixed mindset: Deciding you’ve lived long enough to know how the world works, what’s right/wrong, good/bad, etc.

Adherence to old narratives: There’s a future we forecast in youth of what we expect midlife will look like. (The forecast is usually ‘Sunny with no chance of becoming our parents.’) And when our present doesn’t match that long-imagined future, it can feel like we made some error we hope it’s not too late to correct.

‘I’ve long known what success and happiness look like, and this isn’t it, so I need to change / work harder / buy things to quickly bring happiness about before my time is up.’

That’s the mindset. It reeks of competition, win/lose frameworks, and a couple months shy of 47 I want nothing to do with it.

My youth began late, at age 26, when I finally accepted that I was probably gay. I was young before then, sure, but my hopes and goals and dreams and forecasted narrative were all lies. At 26, I stopped wanting to direct films, stopped wanting a girlfriend who would become a wife, who would then mother our children. Instead, I wanted sex (please, finally), a life centered on art and friends, and, in time, of course (I was young), glorious glowing fame.

I can’t imagine I’ll live past 94 (the folks at John Hancock Insurance estimate I’ll be dead at 83),4 so I’m well past halfway done with this life. And of course I have regrets:

I’ve committed more of my time and energy to my job & careerism than my writing & art.

I’ve only now really come to understand what love is and means and gives me (same with sex), and in not having taken the time to figure all this out earlier, I caused significant pain and hurt.

I don’t have a child. I won’t, likely. I don’t regret this so much as accept it, and think sometimes about what I’ve missed.

But what’s helping me (I hope) avoid a midlife crisis isn’t some rosy ‘accentuate the positive’ optimism, where I weigh my achievements against my shortcomings and find myself in the black. That would keep me trapped in the win/lose framework. I want out of that paradigm, and the way out brings me back to the idea above: that in midlife, you’re closer to death than birth.

This is true only if time is a dimension we move freely through, but it runs in just the one direction; I can’t ever know what’s going to happen in the next hour, or year, or decade. Death, here in midlife, is just as shadowy and mysterious as it was at birth. That’s not exactly a proximity.

My midlife crisis has manifested itself as a certain heaviness I feel sometimes when looking back. The distance between this day and that one is palpably, tangibly vast, and the quantity of memories I’ve made is so abundant, that the act of remembering carries this new, unignorable weight.

It’s tiring, carrying that weight. It’s a really complicated and hard-to-express form of tired I feel now when I look back at certain times of my life: How is it possible that I’m still alive after that thing that happened in … Jesus 1984?

But the thing is that 1984 is milliseconds away, the blink of memory circuits transporting me backward. I’m so closer to my birth than I am to death. That’s not about insisting I’m 46 years young. That’s about an intimacy I’ve acquired with all the many people I’ve been.

They’re all pointing to the many people I’ll inevitably become.

Here’s Lauren Berlant to help: ‘The genre of crisis is itself a heightening interpretive genre, rhetorically turning an ongoing condition into an intensified situation in which extensive threats to survival are said to dominate the reproduction of life.’

The ongoing condition is change. A ‘midlife crisis’ sees change as a problem. Let me tell you on this side of 40 that sometimes the old ways feel stale, and the stability I’ve worked hard to achieve sometimes feels like stagnation. What else can we do but mix it up, join radical organizations, buy new clothes we’ve never worn before?

We allow such revisions and reinventions in kids and teens and 20somethings, and then, it seems, we stop. I think about the first midlife people I ever met: my parents. I remember their 40th birthdays—I was 8, then 9—and I remember looking up to those tall and impossibly old people and needing, or maybe just expecting, them to never change.

That’s the crisis of the midlife crisis, a charge thrown by a jury of anxious children.

We have to keep living. We don’t have to keep score.

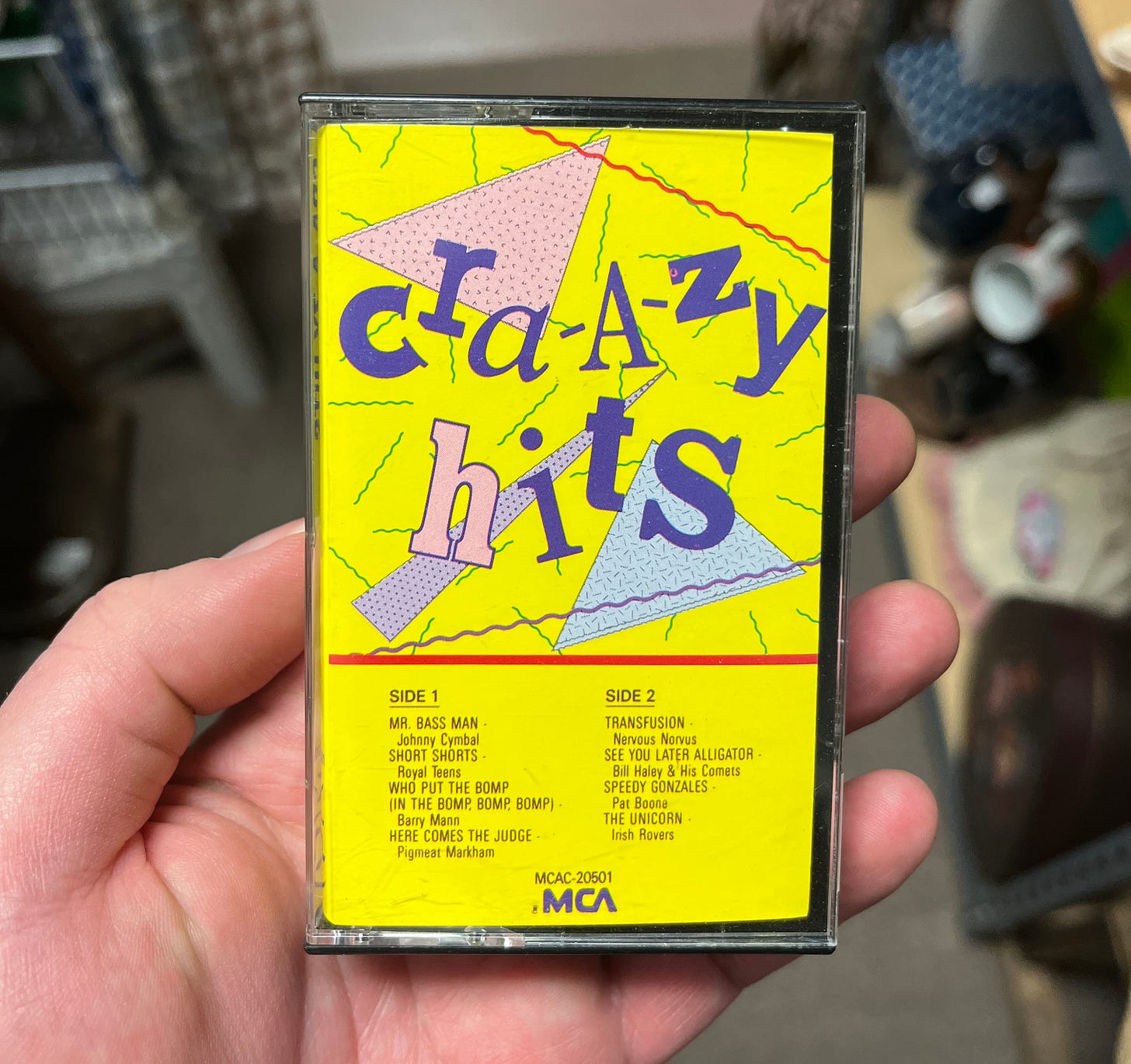

This week’s thing I did not buy at the antique store is this tape going through its own midlife crisis:

Well, maybe Ayanna Pressley and Cory Booker.

Turns out this is both untrue and one way to avoid a midlife crisis, as I’ll get to in a bit.

Clearly winning the SEO wars among the financial press.

It could even be sooner, as I lied about smoking, because whenever forms ask the question ‘Are you a smoker?’ they don’t define the term. Identifying as a smoker feels like lying to you about my age and calling myself an actor.