Are You a Story Chauvinist?

Dear Friends:

Sad election news yesterday, as my fellow San Franciscans once again fell for millionaire-backed policies of lower taxes, greater police power, and forcing people who need welfare to take drug tests. ‘PROGRESSIVISM IS OUT — FOR NOW’ read the front page of the Chronicle, retelling the lie that San Francisco has ever given it a chance (the last progressive mayor we elected was in 1992, and he got voted out after one term). Now the story is that progressivism was a fad, like avocado toast or pickleball, rather than the very simple and humane belief that our policies should help the people who need the most help.

Fitting that this week’s Main Matter is about stories we tell, and our commitment to understanding the world chiefly through narratives. I’m so tired of stories. What led to ‘the tide turning’ on progressivism in San Francisco? How and when did our ‘doom loop’ start, and what can save us from it?

Who gives a shit? Take money and homes from those who have too much and give them to people who don’t have enough. Stop throwing poor and unhoused people in prisons. Don’t tell me how you did it, or who ‘the major players’ were. Just state the facts, like this one: people whose drug charges sentenced them to undergo treatment and training programs (a progressive policy we in CA voted for), had lower rates of recidivism than those sent to prison.

We’re a nation drunk on stories we like and stupid about facts, and this week I’m out of hope for us.

Yours:

Dave

Endorsements

1. Cole Escola’s Oh, Mary!

And yet, some stories are so good I want them told over and over. Oh, Mary! is a play about Mary Todd Lincoln that N and I were lucky to catch while in NYC last week. Escola, who wrote and stars, imagines her as a vicious drunk with too much idle time on her hands. It is the funniest show I’ve ever seen. If you don’t know Cole Escola, it’s time to work this comic genius into your repertory. They are my fave kind of comedian: smarter than most people about the world,1 and eagerer to be seen as a buffoon in it. To avoid any spoilers, all I’ll say is what’s on the program: they’ve written a play that’s so much about Mary Todd that other characters are named things like Mary’s Friend and Mary’s Husband—i.e. that guy you know as having been president during the Civil War, which in Oh, Mary! is given less thought than the shape of the pillows on the divan. Hard to overstate how good it felt not to have to watch another story about the goddamn Civil War, or another bit of historical fiction that works overtime to ‘get it right’ about the past. Everything in Oh, Mary! is deliriously and beautifully wrong. I left with a face that hurt hard from laughing, and a feeling that the fabric of our nation—however tattered—had pieces made more beautiful by knotty queers like me.

2. Synth-Heavy Music

Friend-of-Shenny

I’ve spent many hours this winter listening to more synth than necessary, culling 2h45m of synthy-synths down to 11 tracks3—some of it the moody, droney synth of Seppuku and (SF’s own) Batang Frisco, but I’m clearly partial to the busy plucky synths of Oppenheimer Analysis and Turquoise Days. (And if you’re a synth-skeptic, start with the Jack Stauber track, the pop hit of the mix.) Why do I love busy synths? It’s essentially the music that plays in my mind all the time. Prickly synths looping underneath soaring, clangy guitar noodling should be what day spas play during your massage, if you ask me.

Are You a Story Chauvinist?

It’s cool if you are. Indeed, as your fellow chauvinists argue, you are the essence of humanity.

I’m talking about some of the quotable quotes you see pop up in writing and reading communities, things like:

‘The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.’

That’s Muriel Rukeyser, lifted without context from her poem that opens with, ‘Whoever despises the clitoris despises the penis’. (Which you don’t find posted on many Goodreads profiles.)

Or how about this one from the original mission statement of publishing hub Catapult (before its collapse, that is; they’ve long scrubbed this from their site):

[Prehistoric] humans did not become the revolutionary beings we now consider ourselves to be until we began to share what we know. Swap stories. Consistently. Stories that mattered. It’s our humble point of view that every creative act, every scientific development, every technological disruption is the result of some brand of storytelling collaboration. We say with equal humility that everything in existence, past present and future, is in constant storytelling interaction with everything that came before.

If you say so.

When we imbue story and storytelling with some biohuman essence beyond its aesthetic pleasures, we fall into a mindset I’m calling story chauvinism. Behind every story chauvinist is a belief, if not a certainty, that the game we sometimes play of putting events in consequential order is a practice humans literally can’t live without.

Some story chauvinists talk about our addiction to fiction, but most think that’d be like saying humans are addicted to breathing oxygen. You can find the myth repeated everywhere, if you’re looking for it. Margaret Atwood’s got an especially bad one: ‘You’re never going to kill storytelling, because it’s built into the human plan. We come with it.’

We come with it? Friends, I come not to kill storytelling (not quite sure how anyone would even start), but to question our relationship to it. Who are we and what are we needing when we give story the power of water, air, heartbeat?

One thing we might be is children all over again.

Bear with me while I risk an ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny fallacy here. (Then again, I’m not the one who brought up prehistoric humans.) The oldest stories we have on record are myths, fables, parables—stories meant to carry customs from one generation to the next, instructing the young on Who We Are, and thus Who We Are Not / Who The Other Is.

Note: Leviticus also did this, but nobody’s reading that mess to their kids at bedtime (I hope).

Old stories are as nationalist as anthems. Hearing them realigns us with the cultures we came from, and the people we came from, the people who told us these stories to help us understand the world as they understood it. Thus, we get shaped by the stories we grow up hearing. (An old story that shaped me for years was the one about how boys like girls.)

At any rate, when we think about the art of storytelling, we remember those years we were young and were told a lot of them, and I think we project back to the infancy of our species and decide that humans—not just us individuals—cannot be ourselves without story.

At this point, I’d like to define some terms, abridging from the OAD:

story – an account of characters going through cause-effect chains of events

chauvinism – excessive or prejudiced support for one’s own group (after French nationalist Nicolas Chauvin)

Story is a means by which we can understand the world, but story chauvinists insist it’s the means, our best or only. A cute point I can’t help make here is that story chauvinism is itself a story we tell about stories, and we don’t have to believe it.

A cliche in my field is to point out that essay means ‘attempt’. An essay is an account of the author going through a train of thought. (You’re reading one now.) I think something, or I’ve learned something, and I want to share it with you is the ‘plot’ of every essay.

I’m waving to you here as a happy, happy essay chauvinist. What makes me support essay so excessively? Well for starters, stories aren’t as great as we think.

Let me share with you a quote I liked to share back when I was a story chauvinist: ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live.’

That’s the opening line of Didion’s ‘The White Album’, and for years I heard it as an affirmation of what I thought I knew: We can’t live without stories. It wasn’t until I read more Didion that I understood that the subject of her famous sentence isn’t stories, but our telling. Here’s critic Michael Silverblatt on the matter:

[Didion] has a mind that aggressively finds … the places where you’re trying to burnish your weakness with pretty words. And her attitude is ‘Everybody’s lying and life is the story we’re telling ourselves in order to stay alive. And an artist sees through the story. Sees through the fakeness of the story to … the coping mechanism functioning in a true situation of devastation.’

The world is deeply unfair, or too enormous and complex to make any clear sense of. This is why people flock to priests or gurus or influencers or Jordan Peterson-types: they want someone to ‘make sense’ of ‘all the chaos’, and so they find a professional liar storyteller to think it through for them.

Note the way Catapult’s mission statement above conflates sharing what we know with telling stories. Is that what we’re doing? And how are we sure of the difference between ‘what we know’ and ‘what we think we know’?

Here’s something I know (or think I do) that I want to share: we have a tendency to make story more valuable and trustworthy than it is, and in doing so, we shut down the potential power of other forms of understanding the world.

How do I tell you that story? Indeed: that I can’t tell you this as a story leads us to belittle the very quality or utility of the knowledge. Must not be worth knowing.

Story chauvinism perpetuates the lie storytelling has a value above all other means of sharing knowledge, all other forms of art. This is true only if you’ve decided you want it to be. Why, for instance, is the universe not made of songs? of poems? of jokes?

Here’s how story chauvinists usually shit on essay:

Opinions are like assholes. Everybody’s got one and they all stink.

Setting aside the fact that this is also true about stories, story chauvinists lament the bounty of opinions, suggesting that story’s value lies in its rarity. But I think it has less to do with supply and more to do with essay’s threat to our sovereignty. Let me try to explain.

As story leads us through a string of events, we avatar ourselves inside the protagonist and go through the experience in less time and with less risk. Story packages trials and travails in such a way to deliver its reward without the audience having to do the work.

In contrast, opinions—or, to use a less hated term, knowledge—are more like the prize one wins from story’s trials, from having gone through an experience and reflected back on it, and on the whole prizes don’t share well. Prizes feel precious to us, little trinkets we won that we get to show off.

This, then, is how our resistance to listening like bedtime toddlers to each others’ ideas is about sovereignty, because we all already have our own. And as safe as story makes it for us to ‘become’ someone else for a while, it often feels unsafe to hear others’ ideas, because what if they fuck with the ones we’ve won?

If there’s something else true of humans as a species, it’s that we don’t like our egos shattered.

Talk about shattering egos—a central trope in queer theory—gives me a place to end on, because as I’ve written before, there’s something very heterosexual about story chauvinism. Consider again its complaint that opinions are like assholes. For story chauvinists, the asshole is a site not of creative pleasures but sodomitical ones (or it’s void of any pleasure at all, save voiding).

When you’ve seen a lot of anuses, and enjoyed your time spent with them, the asshole becomes something else: a desirable part of a person, one that every human shares, across cultures and genders. Suddenly something special happens: Opinions are like assholes! Everybody’s got one!

Why can’t they be essential to our humanity? When you start to see people as being full not of shit but of thoughts, beliefs, worries, hopes (maybe much of them tied to the ‘story’ of their lives but by no means forming into any narrative), than each person you encounter becomes a universe in their own right, a thinking, teeming galaxy to explore.

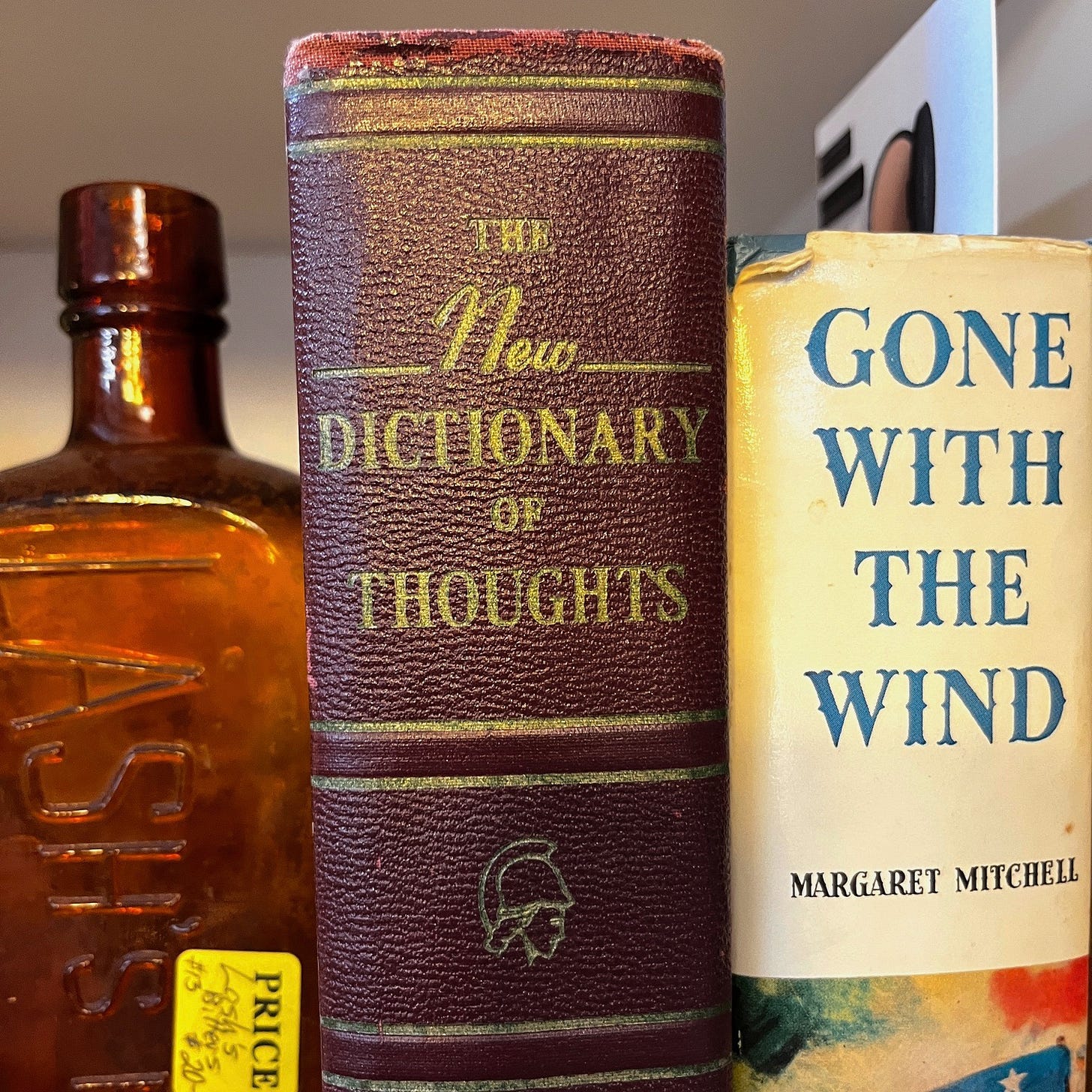

This week’s thing I did not buy at the antique store is The New Dictionary of Thoughts, which like lord knows how they got classified.

There’s a moment toward the end of their batty, beautiful pilot, ‘Our Home Out West’, where Escola plays the town harlot (among other characters), and the little boy in her care asks, ‘How come people hate you?’ Her response, in all of 35 seconds, is one of the sharpest and most compassionate explanations for queer/transphobia I’ve ever heard.

The SK-1 warrants an endorsement of its own, not just for its sampling ability (Gene from Bob’s Burgers probably has one), but for its 13 present envelopes you could choose to set the attack-decay-sustain-release of your synthesized tones.

Then I decided to make a companion mix of almost-as-good songs: ‘Decay / Release’