Dear Friends:

Are you feeling Spring? I’m feeling Spring in the jism-y smells of blooming trees the mornings I open all the windows, and in the whiff—faint but real—of the semester’s end I get every time I look ahead at my calendar.

My pal Heather used to talk about Winds of Change, how any time wind picks up, to where you really feel it, it’s a sweeping out of the old and in of the new. We live up on a high open hill, here’s our view from the 2nd story looking oceanward at some weird clouds:

These days, it’s like the wind never stops. What to do with winds of change that are a constant?

Yours:

Dave

Endorsements

1. May Day

I was heartened by the Hands Off! protests around the country earlier this month—the more headlines on 50-states-wide mass disapproval and dissent the better—and I was also glad to see the organizers planning another mass day of action on May 1, International Workers Day, more commonly called May Day. I believe in workers because I am one, they are my people, I will fight for only their rights forever, and I believe in unions because I’m in one, and my quality of life is better by the work our union has done over the decades. I want to do everything I can to promote an idea of government by the people who work to run the government, to counter our tendency to obsess over the administration. Growing up in Northern Virginia, a government of laborers was my everyday—maybe half my friends’ parents worked for the federal government in some capacity. If you want workers returned to the government, and thus hopefully vice versa, find a May Day rally somewhere near you.

2. The Residence (Netflix)

Talk about a focus on government workers! If you’re not familiar, this is a pretty great Shondaland whodunnit, about a murder among the White House’s residential staff (who, apparently, work there regardless of who’s living there), done in the vein of Knives Out or if Wes Anderson did a murder mystery and was way less twee and much more civic-minded. Uzo Aduba’s Cordelia Cupp is an irresistible detective: gorgeous, calm, comfortably the smartest person in every room, eccentric without being a pill about it. The plot twists each episode to keep you watching, but I can’t stop watching Cupp watch her suspects. I know it’s all scripted, but she’s so good at using eye contact to get people to say more. Behold:

All this in a show that repeatedly makes the case that the people who work for our federal government, and the work they do every day, are glorious things we need to value and protect.

8 Things I Learned Watching My Colleagues Teach

It’s any Thursday last October, last November, somewhere in the deep dark dregs of the fall, and I’m sitting in my office staring somewhere at the floor. 6:10pm. Class is starting soon, and I feel like a penny in the bottom of a pocket in a pair of forgotten pants.

I’ve had this feeling before, fall 2004, tasked by my MA program to go teach two classrooms of undergraduates how to write. But I’m trying to learn how to write. With only a week of summer-camp-style prep behind me, I dreaded having to face those students, seem like I know what I’m doing. My classes were 8am and 9am, MWF, and every morning that first week I had to wake up early to leave time, 20–30 minutes, to spend in the bathroom, my body bent over the toilet, guts wracked and heaving.

In my office last fall, I repeat these words in my head: I don’t want to go in there. The classroom, I mean, a place I normally feel as comfortable in as my bed. I watch the minutes fall, one after the other, until I don’t have a choice but to go in there.

The class, ‘The History of Humor in Nonfiction’, went fine. Other students not in the class would tell me they were hearing great things about it. My evaluation scores were high and comments were kind. But something was up, and once the semester was over I tried to figure out what it was.

Part of it was that I was repeating a class for the first time. I’d taught a humor class four times before, switching it up each time. But I’d had a grueling ’23–’24, and to give myself a break I taught the Fall ’24 version the exact same way, week by week, as I taught the Fall ’22 version. Same texts. Same assignments. Same lesson plans as before.1

Something about that quickly felt like death to me. Everything was new to the students, but because it wasn’t also new to me, I lost enthusiasm to go teach it. The death feeling wasn’t just about course content. It was about me. I was seeing a classroom the same way I’d been seeing it year after year. My ideas about teaching had gone stale, and I needed some fresh air.

In December, I emailed my colleagues:

12 years into this job and I've hit a wall, I can tell, in my approach to seminars. I'd like to find new ways forward. I'm emailing to see whether you'd be open to me sitting in on one of your class sessions in the spring. My aim is just to sit in the back and watch how other expert teachers do their thing, to gather inspiration on how I might better do my thing.

Three of them replied letting me in. So three nights in February, I sat in the back, waved at students when my presence there was explained, kept my eyes and ears open, and wrote a lot of notes. Quickly, I saw two things, clear as a slap in the face:

I was teaching like a scholar, not like an artist.

I had been working way too hard.

Here is a list of what I learned (many of them v. obvious):

1. Laptops are useful

Each week, I come to class with 2-3 pages of notes I’ve typed for myself in MS Word, much of which I write on the classroom’s whiteboard, and my handwriting is terrible. (Related lesson: write larger letters.) I watched my colleague K.M. Soehnlein do a tight but thorough lecture on the 3rd person,2 and the production values of his laptop slideshow were, he admitted, low: ‘It’s just black text on a white background,’ he told me, ‘but it gives us all something to focus on.’ I know, I know, this ‘tip’ should be obvious to someone who’s been teaching for 20 years, but here we are: Airplay a laptop!

2. Consider learning by doing more than by hearing

All of my colleagues did some form of small-group discussion and/or student presentations (see #3 below). My approach instead is to come in with Everything I Think Students Need To Know, and then do my best to squeeze it all into the allotted time. Watching teaching, I found that, if you give them space to do so, students will speak to whatever the class’s main concepts are. If I’ve first lectured on the concepts, the value of their contributions is diminished, redundant. Instead, prompting them in ways that lets them bring the topics up allows me to affirm their understanding of, say, the narrator-protagonist divide in personal essays, and then elaborate on some of its nuances and applications. Doing this sacrifices the quantity of things I’d like to cover for the quality or stickiness of things retained.

3. Small groups aren’t always a certain kind of hell

I hated small groups as a student. Hated them, because inevitably somebody didn’t do the reading (okay, sometimes it was me) and it always fell to the extrovert (hi) to get anyone to say anything. But something I noticed was that students really like to show off their insights, as though reading assignments were like scavenger hunts and everyone found a cool trinket. Small groups are a way for them to share those with each other, and work together to find overlaps or connections to bring to the whole class—where my job becomes listening very closely and connecting their findings to course concepts. It’s learning by doing, by being put in active practice together, rather than by listening and writing down whatever I say.

4. Only teach texts you love

This from my colleague Laleh Khadivi, who’s teaching Teaching Creative Writing this spring. More obvious advice I needed to hear. I teach a lot of texts I feel I should, esp. in ‘The History of Nonfiction’.3 No longer. And I like the imperative behind this: To serve all the different kinds of students I’ll have, I need to love a lot of different kinds of books.

5. Discussions need frameworks

One thing I struggle with as a teacher is how to get different people to learn together. This student always wants to talk about whether a draft is believable or not, and this student learned a lot of ‘rules’ in undergrad they like to point out the breaking of, and this student likes everything to be in a more lyric mode, and this one learns by devil’s-advocating everyone’s points. When the group discussions I observed went flat, or weren’t coming together, it seemed there was a lack of framing or structure. An absent objective. I wondered, What are discussions for? What are we trying to discover together? Looking for answers, I got an idea: First ask students what we value or desire for the subject at hand. Like in a workshop: What do we hope to see in a ‘good’ draft? Too often the values that frame workshop apply to published essays, so we talk about how there are no wings on this caterpillar, how it’s moving too slowly and only on the ground, instead of flitting about in their air like a beautiful butterfly. This idea is new, and needs more work to prevent a homogenization of viewpoints, but I struggle with what’s instructive for everyone by opening the discussion up to just anything.

6. Communicate your approach or style

There were moments watching my colleagues when discussion had strayed so far off topic, people chiming in with random thoughts, and I felt so impatient and so unhappy. I’ve since heard from colleagues their thoughts about the importance of letting students find their own ways through a discussion, and about meeting students where they are. I hear them, but don’t relish being in such a classroom. This is a personality quirk I accept, which leads to a teaching style I exhibit. It’s important to communicate that style early—specifically in the syllabus. There, I plan to describe how I’m most comfortable inside a clear plan or structure for the class, but I also want to be flexible and open to straying from the plan when we’re chasing the heat of something. It’s like me saying, Here’s where I’m coming from, and I’d like y’all to rein me in sometimes.4

7. Work with / against gender dynamics

On the whole, female students wait their turn to speak, or wait to be called on. Male students just speak into the room whenever they have something to say. This is a kind of gender dominance I want none of in my classroom. Lots of folks use a self-directing ‘step-forward, step-back’ approach, asking folks who speak a lot to wait before speaking again, but I’ve found people are too entrenched in their communication styles to voluntarily change. So I’ve long had a syllabus policy that everyone has to raise their hand and wait for me to call on them, to leave space for those (of all genders) who don’t feel comfortable speaking into a room. I’m pretty good at remembering the order of folks whose hands have gone up, and we get to each in turn. Now, I’m incorporating the progressive stack approach to discussion, where anyone whose voice has not been dominant in the discussion gets to leap to the top of the stack when I see their hand.5

8. Lecture about the world, not about our craft

I watched my colleague D.A. Powell teach his ecopoetics seminar about birds, and there wasn’t much lecture, but the lecture he did provide was a recap of bird anatomy with a specific focus on feathers. There was a handout on the parts of feathers, he discussed the functions of feathers, and the class listed all the ways feathers figured in human experience (e.g., quills, dusting, fletching, jewelry, millinery, etc.). Teaching as a scholar, the way I have for 20 years, I wondered What does this teach about writing, esp if you don’t write about feathers? And that question beats at the heart of my trouble: I’m stuck on ends over means. I claim to want students to feel inspired to write essays of enduring strength and beauty, I claim to want them to show me aspects of the world I can’t see myself, then I go and lecture on the intricacies of psychic distance. Going forward, I’ll aim to focus less on craft—i.e., how to render the stuff of the world—and more on leading students toward fresh ways to look at the world, know it, rethink it, etc.

What I learned from watching my colleagues teach is that now that I’m a professor (with no adjective), I want to stop professing—if we take the literal denotation of ‘to claim that one has a quality or feeling, esp. when this is not the case.’ Instead, I want to be a writer a bit further along in his development than the students are, showing up as myself, with as many doubts as I have answers, but always ready, like them, to learn again.

Like this post about worrying and revising teaching practices? Here’s another:

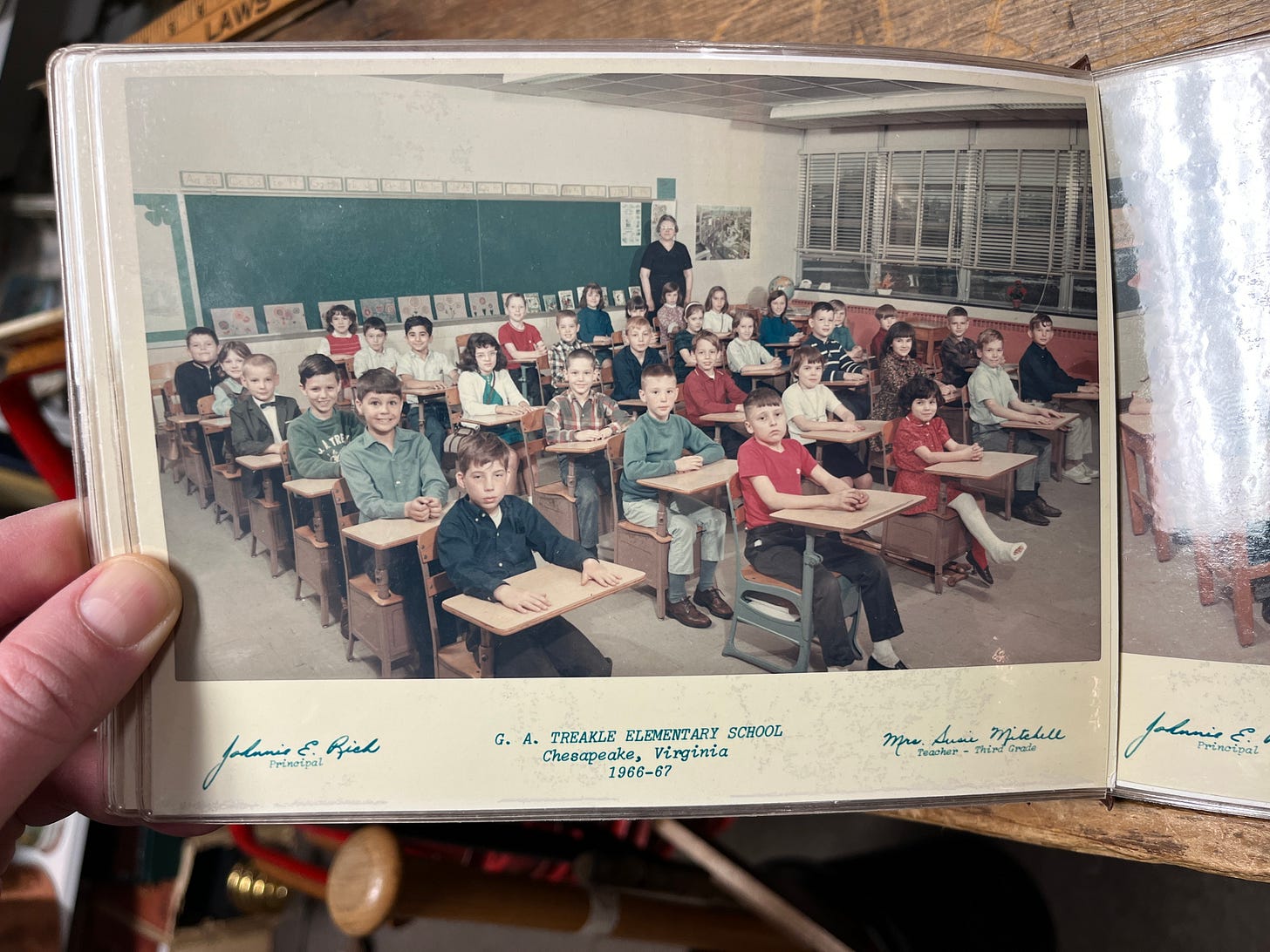

This week’s thing I did not buy at the antique store is this 1967 photo album of classes from G. A Treakle Elementary in Chesapeake, Virginia.

We’ve all taken such classes, where it’s clear the professor has been teaching everything the same way for years. After doing this job for so long, re-doing a previous course seemed like a smart idea, like bookmarking a failproof recipe.

One cool bit from his lecture: if 1st person lets you play with voice and 2nd person lets you create effects of alienation, 3rd person is all about giving yourself flexibility.

Another thing I realized last fall is that our nonfiction seminars were all designed with a scholar mentality. (And I should know, I’m the PhD grad who designed them 10 years ago.) It’s another approach that’s about coverage and packing into minds everything they should know if they’re to become Masters in Fine Arts. And so it’s time to redesign our curriculum with an artist mentality, which maybe I’ll make a future Shenny about.

This is collaborative pedagogy, which incidentally was the thing Laleh was teaching about in the Teaching Creative Writing seminar I observed. Another smart point from that class: Both a syllabus and a classroom are like a piece of writing—you always need to expect your audience will finish it via their engagement. You are not responsible for (or even capable of) making those spaces complete.

I’m also considering doing away with pronoun-sharing and requesting that everyone, me included, adopt ‘they’ pronouns in the classroom. This is after some recent thoughts from my friend Cammy Grass, who’s been writing about the new inflections of Trans Visibility in a fascist regime committed to obliterating trans lives (‘Visibility without safety is just exposure,’ she quotes). When we ask everyone to share their pronouns, what kinds of attention are we drawing on trans and nonbinary students at a time when the whole country is glaring at them? If we’re all nonbinary together, does this make for a more inclusive space? (Trans and nonbinary friends, I’m open to advice here.)

I just read an article about the brutal consequences of using AI in the gaming industry that used they pronouns for everyone quoted, and it had the wonderful effect of equalizing all of the voices and foregrounding the ideas they were each expressing. It almost felt like a magic trick.