My Fellow Shennyer:

While I get that conversations about politics are really about fellow-feeling—we’re trying to find our people amid these divisions we keep hearing about—when you’re in a politics conversation, the point seems to be more about righteousness than desire. Not What Do You Want, but What Should Be.

Being past the age when I lived under a vast ceiling of shoulds, I opt out of politics conversations. But then (per my thinking about self-expression I got into a couple Shennys ago), I realized my job in any conversation is to listen, think for myself what I want or feel, and then say it.

If everyone else in the room disagrees, that’s okay. I enjoy now how it feels to say, ‘I disagree,’ without having to ‘defend’ my disagreement.

If I have a core political belief as an American, it’s that old phrase on our coins: E Pluribus Unum. I’ve given this a more in-depth treatment here, but I get big warm patriotic feelings when I think of this one nation formed by the many.

Some of us Americans think that only whites deserve to have power. Most of us, as we’ll see in today’s Main Matter, don’t believe trans people exist. I, in a politics of desire, want trans lives and expression to be honored and protected. Each of us, in theory, gets the same voice. What makes the media landscape, social and otherwise, such a drag these days is how fearful reactionary voices get all the bullhorns, while the rest of us wanting to be heard have to rely on breath support.

I wouldn’t call Shenny a bullhorn; it’s so easy to turn off. Here’s to media it’s easy to turn off, and the media we’d never want to.

Yours:

Dave

Endorsements

1. Release McCracken, the Substack of writer Elizabeth McCracken

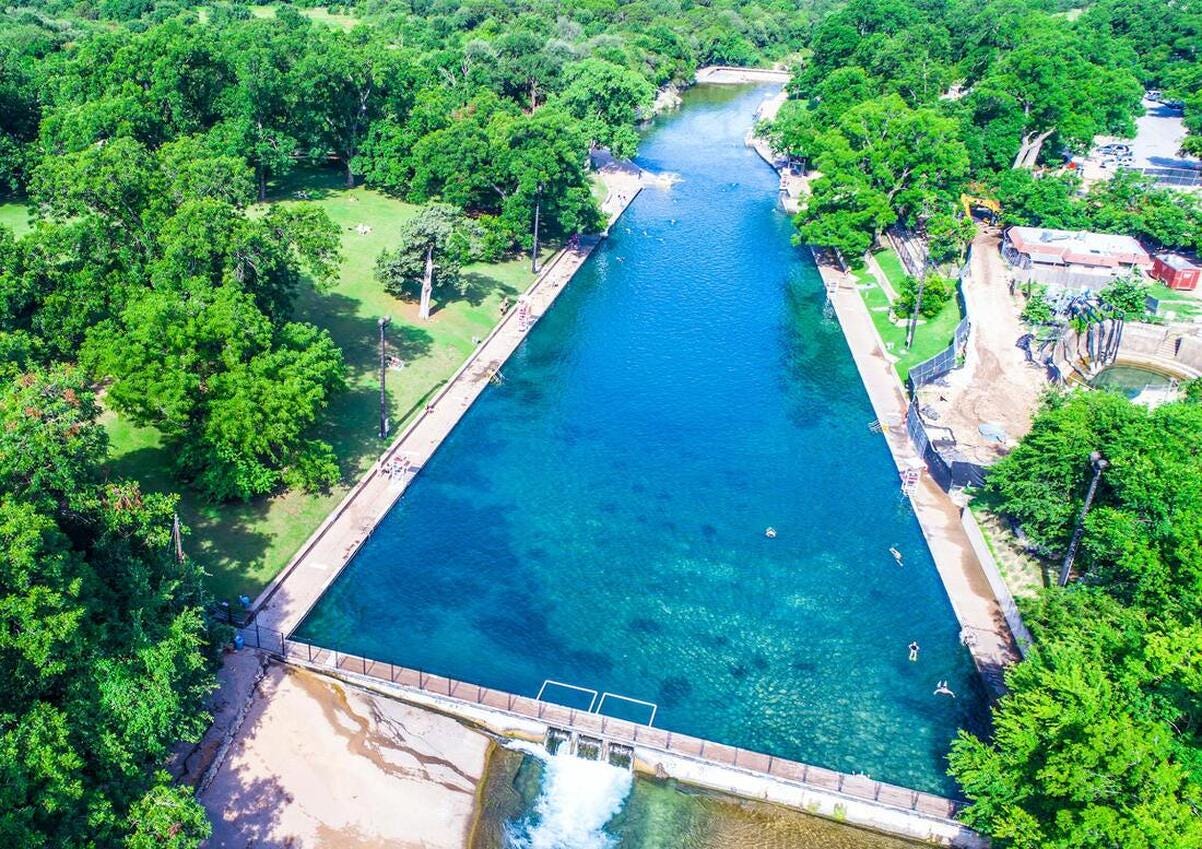

How could I not endorse a Substack of swim reports? Impossibly, the novelist Elizabeth McCracken wakes every morning at 4:30am to get up and go swim in Austin’s enormous Barton Springs Pool, which despite not being a natatorium merits a pic:

Then, some mornings, she posts about it. What I love about swimming is that there’s nothing to notice, other than your body and the water. Your eye doesn’t get distracted like it would on a run. And yet—perhaps given the outdoor setting, perhaps given McCracken’s expert novelist’s noticing—her reports are funny and full of life:

A fine swim, though one guy was swimming so determinedly and quickly without taking any sighting strokes that it took all my effort to get out of the way, and I said, “Look out! Look out!” as he passed me—though of course he couldn’t hear me: his ears were underwater. I also think he should look inward.

My last length it was light out. Three buff topless men stood in the shallows, hands on hips. Anyone who didn’t know might think they were posing as superheroes, hoping to be admired for their admitted magnificence, but I knew: the water is cold. It takes a moment. They dove in just before I passed, and I could taste the perfume off their bodies—deodorant or lotion—as the water washed it off them & towards me.

2. Larry Mitchell’s The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions

I didn’t know that all my life I’d been looking for a fable about queers loving and working together as they prepare to destroy the patriarchy—or ‘the men’ in Mitchell’s parlance. ‘The faggots’, Mitchell writes,

find it hard to be near the men. The faggots know that you choose to either obey the programs or to defy the programs. They find it troublesome to be around those who say the program is inevitable.

Over the course of this short book, the faggots and their friends help each other stay alive and sane in Ramrod, a place run by the men. These friends include the women, the [drag] queens, the [radical] fairies, the faggatinas and the dykalets. Even the ‘queer men’ who dress and walk among the men, ‘using all the tricks their fathers taught them’ and at night go out and cruise the faggots. It’s a book full of beauty and compassion, generous in its spirit. As often as I want to decry Lindsey Graham–types who get themselves the pleasures of gay sex without any of the open solidarity with us, Mitchell sees the cruising ground as a place for potential:

Here chance disappears. Here release is guaranteed. Here the queer men meet the faggots. And here, without knowing it, the queer men and the faggots commit themselves to each other.

Dropping the T from LGBT

When, in your past, did the other kids start pairing up as girlfriend-boyfriend? And when you saw it happening, how did it feel? Were you ready? Were you even one of the bold kids who slipped a note into a desk, or—holy cow—walked up to somebody and asked? Or were you a little terrified, suddenly coming in last in a race you hadn’t even been told about?

When it happened to me, around age 10, I recognized it. Oh, right, this. That girls were girls and boys were boys and soon they liked each other was the fact underlying every story I’d ever been told, from It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown to the story of my family’s creation. It felt as obligatory as when everyone started wearing Chuck Taylors; this is what I had to do if I wanted to be like everyone else.

Why did I want to be like everyone else? Because I felt like nobody else. It’s something I’m trying to capture these days in the memoir, being told it’s good to be special, but feeling the wrong kind of special.

It could come at any moment, the feeling. I kick the ball just far enough that I actually get on base. I do the math problem correctly at the blackboard. I unwrap the paper and there it is, the new Zelda game. And without thinking I’d be moved to celebrate, jumping up and down a certain way, flapping my arms and hands a certain way, squealing a certain way. My pure expression, and then the eyes of everyone around me, their fallen faces, saying No. Not like that.

That quashed joy. Each time, such a small correction. But then you line up that endless string of them.

I shouldn’t need to tell you that trans kids are under attack—and not just in states that have fallen to fascism. (If this is news to you, here’s a primer.) The nonsense of it all, the lies being told everywhere, and the damage being done are painful to watch—especially since recent polls show that GOP lies about trans youth are working. More people than ever believe one’s gender is set at birth, and an enormous 70 percent of Americans believe that trans issues shouldn’t be taught in elementary school.

To support, say, Black History Month but not trans education in schools, seems to imply that you do like kids learning about who they are, just not trans kids. Or maybe you don’t believe trans kids exist? (The origin of trans people predates that of race, by the way.) Or maybe you believe that by ‘holding off’ on this education, you can delay kids from ‘turning into’ trans kids?

Listen: these beliefs will fuck kids up. If you feel that 8, 9, or 10 is too young for a child to learn about what it means to be trans, no judgement, but such beliefs are going to fuck up the lives and minds and bodies of the trans kids in our schools. I promise you.

How can I promise this as a cis man? This brings me to what inspired this Main Matter. Naive as I am, I only recently learned about the ‘LGB Drop the T’ movement among (mostly online) queers, who post anti-trans hate under the guise of ‘rational arguments’ that sexual orientation ≠ gender identity/expression.

I shouldn’t be surprised to find that queer folks can be transphobic. After all, I was one of them, for a while.

Back in 2006, just a couple years after I came out, I read an op-ed (did Andrew Sullivan write it?) about an anti-discrimination bill in Congress. The argument went that gays and lesbians had fought for decades to get equal rights, and now here were transgender folks trying to be included on the bill. But sexual orientation ≠ gender identity, so fight your own fight, people.

I bought that argument wholesale. I didn’t want to discriminate against trans people, but I didn’t see why I had to be lumped in with them. People can become trans and then marry someone of their birth sex and they’re basically a straight couple! We have nothing in common!

To me, it felt like trans people were muddying the waters, with their confusing bodies and invented pronouns. Trans people hadn’t lived our experience as queers. I couldn’t see any common ground between us, I could only see our difference from each other.

Which brings me, I’m afraid, to the JK Rowlings of the world.

The JK Rowlings of the World are very keen on differences and distinctions: they aren’t, they claim, against trans people or trans rights; they just won’t accept that trans women are women, having not lived the experience of being a cis woman in a patriarchal world.

In other words, fight your own fight, people.

Underlying all these arguments, my old one and that of the JKRsW, is the belief in a justice paradigm of scarcity. It goes like this: the people who have all the rights—I’m going to take a page from Larry Mitchell and call them the men—only have so much rights to hand out, or are willing to hand out rights only to a small, select group.

In this scarcity paradigm (like all bad ideas, this one is the men’s) the rest of us have to compete for favor. Which means drawing all kinds of distinctions, adhering to norms and boundaries the men created to better suit identify themselves. Trans women are not women is not, then, a feminist idea. It’s what the men always already believe.

When you think that rights are due only to some people, and are due to those people based on their born identities, and yet you still don’t have equal rights, denying rights and justice to those who also want them seems like an especially craven move. And just misguided, your eyes on the wrong kind of difference.

The argument for our rights and respect doesn’t hinge on proving to the men that we’re more like them than not, it hinges on demanding that the men accept our (shared) difference. It demands the end of discriminating because of difference.

This is why the fight for trans rights, and the rights of trans kids, is all of ours to fight.

What changed for me, all those years ago? What kept me from becoming another JKRW? Something un-extraordinary happened: I met a trans person. Then another, then many. I taught trans students, read their stories. And in hearing about their lives of quashed joy, the constant confusing correction of their pure expression, I realized we had nearly everything in common. Everything essential, we shared.

What I mean is that I know firsthand what it’s like to grow up wrong, with no visible people like you living in the neighborhood or working at your school, never hearing stories about who you are. The people who raised me and gave me health care and an education kept me 100% free of any positive depictions of gay people, and yet here I am, so extremely homosexual.

I don’t know how any queer, or ally, could believe that denying trans kids education and affirming care could have some positive effect. Ignorance helps nobody. (Well, nobody but the men.)

In writing, today, about our shared struggles, I’m not erasing every boundary; my experience growing up as a cis kid is very different from that of a trans kid. Those boundaries are essential in building respect and understanding. But what I have to understand trans people is my queerness, that fundamental story. Dropping the T from LGBT will only bring us all further away from understanding.

This week’s natatorium is the neatly asymmetric De Heuvelrand swimming pool in Voorthuizen, Netherlands:

Thanks, Dave! I'm always surprised and saddened to learn of the subtle differences that drive discord and division among people, in particular among groups that have been unfortunately marginalized or oppressed.

Thanks for this, Dave. I so appreciate and identify, for my own difference, not fitting reasons, despite my cis straightness, with what you write here. Love, Peter